The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first official African American units in the United States during the Civil War, was comprised of men from Berkshire County, Mass. and Litchfield County, Conn. The story of the unit, including its struggle for equal pay, was depicted in the 1989 film “Glory.” The MASS 54th Trail is the most recent addition to the African American Heritage Trail, a program of Housatonic Heritage.

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first official African American units in the United States during the Civil War, was comprised of men from Berkshire County, Mass. and Litchfield County, Conn. The story of the unit, including its struggle for equal pay, was depicted in the 1989 film “Glory.” The MASS 54th Trail is the most recent addition to the African American Heritage Trail, a program of Housatonic Heritage.

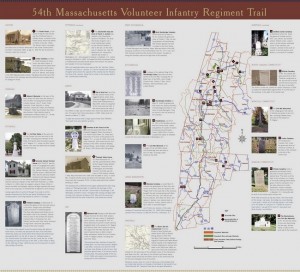

in 2011, a new book, “On the Other Side of Glory,” was written by David Levinson and Emilie Piper and published by Housatonic Heritage. The MASS 54th Trail includes 24 sites – homes, churches, cemeteries, monuments – in twelve communities, from Dalton, Mass. to Sharon, Conn. Each site is associated with an African American man or group of men who served in the 54th. A self-guided tour brochure will be unveiled at the reception. This brochure directs visitors to places regiment members lived, went to church, are memorialized, and buried.

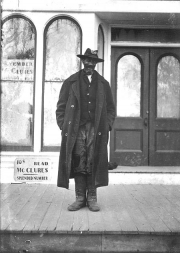

The “MASS 54th” interpretive trail is the most recent addition to the African American Heritage Trail, a program of the Housatonic Heritage. The African American Heritage Trail celebrates African Americans in the Upper Housatonic region, ordinary people of achievement and those who played pivotal roles in key national and international events—W.E.B. Du Bois, Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman, James Weldon Johnson, Rev. Samuel Harrison, James VanDerZee, and others. More information about the trail can be found at www.africanamericantrail.org/54th-massachusetts-volunteer-infantry-regiment-trail/.

54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment Trail

A self-guided motor tour of 24 sites in 12 communities from Dalton MA to Sharon CT

honoring the men from Berkshire and Litchfield counties

who served in the “Glory” regiment by directing visitors

to places they lived, went to church, are remembered, and are buried.

When victory is won, there will be some Black men

who can remember that, with silent tongue and clenched teeth,

and steady eye and well-poised bayonet,

they have helped mankind on to this great consummation.

— Abraham Lincoln